Electile dysfunction

The most annoying and pointless debate on the left

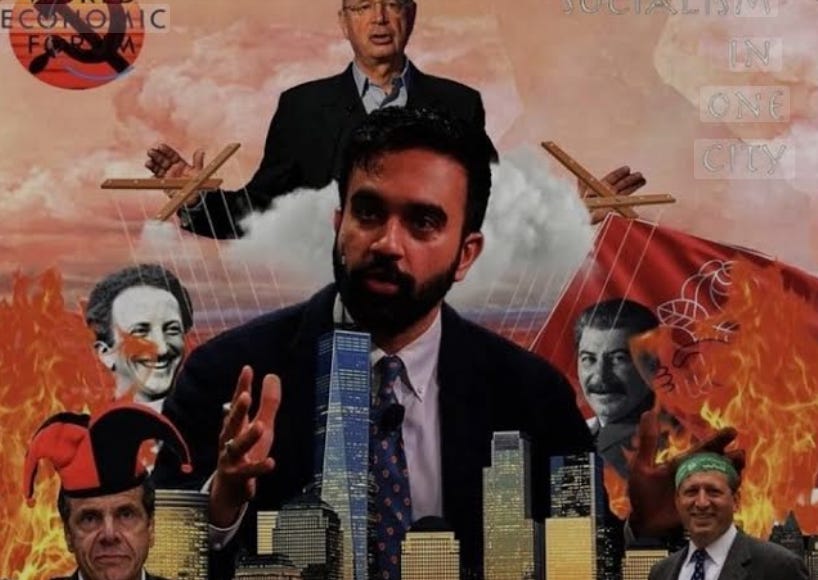

In case you haven’t heard, New York City may soon have a radical leftist mayor. Under Comrade Zohran we will immediately set upon building the Islamo-Bolshevist caliphate, give all buses pronouns, and turn Dimes Square into an open-air gulag. But while it’s surely an exciting time for all of us baristas with blue hair, septum piercings, and degrees in underwater basketweaving, this development has unfortunately caused the resurfacing of a perennial debate about what relationship, if any, people who consider themselves politically ‘radical’ should have to elections and the Democratic Party.

Surely, you’ve heard them all by now: that both parties serve capital or that there are nevertheless consequential differences between them, that those who don’t vote have no right to complain or that those who do are legitimizing the system, that those who fail to vote against X are responsible for the resulting loss of women’s and LGBT rights or that those who vote for Y are responsible for bombs dropped on children, that the Democratic Party is either the only realistic vehicle for social change or that it is the graveyard of social movements; that we cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good or that the lesser evil is still evil. What strikes me about this discourse is how little it has changed during the entire time I’ve been politically conscious (starting with the 2000 election allegedly spoiled by Ralph Nader and a few hundred voters who failed to appreciate just how bad a Bush presidency would be) and how little coherence there is to the whole thing – as if multiple broken records were being played side by side.

The anti-voting arguments are easy to pick apart. For instance, many of the people who usually assert that your vote doesn’t matter and that there’s no difference between the two parties are also the ones who spent much of 2024 shouting that anyone who voted for Harris has Palestinian blood on their hands. But either voting is a meaningless gesture in a rigged system where nothing changes, or a profoundly important act and the deepest expression of your true political ideals, with grave consequences for which you and your immortal soul bear solemn responsibility (an extremely 'liberal' worldview, by the way) - it can't be both. In any case, the blood that’s flowing will continue to flow regardless of how clean your own hands are.

The logic of a ‘protest vote’ (or protest abstention) also doesn’t hold up to the slightest scrutiny. Votes aren’t recorded as statements of individual intent, only as part of an anonymous aggregate, and your protest vote or principled abstention will be counted the same way as a true third-party believer or someone who got stuck in traffic. Nor will it ‘send a message’ to the losing party, who will only take away the message that is most convenient for them, as we already saw after 2016. Ultimately, any such calculus would require there to be an organized bloc that is in a position to publicly send a message in the first place, by withholding votes or making demands in exchange for their support as part of a tactical coalition. No such entity exists today - only a smattering of media entrepreneurs and mass appeals to individual moral conscience in the privacy of the voting booth.

But none of this means the Democrats were right. For one thing, Harris supporters who blame her loss on pro-Palestine abstentionists are oddly resistant to the point that if this were indeed true, then Harris could have prevented the loss by simply changing her position or rhetoric on the issue. Somehow, an uncoordinated statistical category is saddled with more agency and responsibility than a political candidate and their party, even though only one of these entities has billions of dollars in funding and a centrally managed campaign staff. Another common line is that leftists should vote for Democrats but ‘hold their feet to the fire’ once they’re in office – yet it’s never explained by what mechanism this orthopedic intervention is supposed to occur if one’s votes and support already come pre-guaranteed in every election.

Throughout 2024 it was common to hear the refrain that the two parties were actually the same and that the outcome of the race would not make a difference, as both the deportations and the genocide in Gaza would continue either way – proclamations that have since largely been replaced with awkward silence once the new administration set about thoroughly demonstrating just how much of a difference it can really make. Nevertheless, it’s important to understand those statements for what they were and remain – not arguments of fact or attempts at persuasion, but moral bravado and bluster by people who felt overwhelming genuine revulsion at the Democrats’ spineless complicity and could not think of a stronger way to express it. In other words, statements about the efficacy or non-efficacy of voting or the intractability of the two-party system generally don’t reflect actual beliefs about reality, but function as social signals of the speaker’s chosen political aesthetic – whether you fancy yourself as the Radical Revolutionary Who Rejects the System, or the Sensible Adult in the Room Who Gets Results.

Another thing to understand is that people are actually arguing about several different (albeit related) things all at once without realizing it. Those include: a) acknowledging political reality by understanding that that there are currently only two possible outcomes and one of them will definitely occur, b) preferring one outcome over the other, all things considered, c) personally deciding to vote for that outcome, d) actively urging others to vote for that outcome, e) arguing that people not only have a duty to vote for that outcome but also to join you in advocating for everyone to do so, and f) publicly endorsing the outcome as an undiluted good and shooting down any criticism or questioning (perhaps because you've decided this is necessary to increase enthusiasm and turnout). Between all of these there is a vast gulf filled with factors like collective action dilemmas, coordination problems, and the electoral college; the idea of a direct moral link between one’s individual vote and the actions of those in power is tenuous precisely because the entire system is explicitly set up to put as many mediating and refracting steps between those two things as possible .

What I wish people would take away from all this is not an argument for or against voting, but a proper understanding of it as a separate sphere from one’s radical commitments. When you vote, you are exercising your (very limited) privilege as an individual bourgeois subject to choose certain particulars of how the regime you live under regardless will interact with you and others. But there is no reason to place this choice (or refusal to choose) at the core of your political identity, any more than you would the way you file your taxes. If pressed on a personal level, I would recommend taking the half hour out of your day to have a miniscule impact on the likelihood of getting the outcome that’s slightly less harmful based on a sober assessment of the grim reality rather than ego-stroking slogans. But no one should be under the delusion that this constitutes a *political* act in any meaningful sense of the term or that the best use of one’s *political* energies – that is, what people do when they think, agitate, and argue together, issue public statements, or plan organized actions – is to perform free volunteer campaign labor and PR work for a party that has its own massive stockpile of funding and resources.

This is where the voting skeptics have a point. If there is to be a legitimate left-wing political movement, its popular perception must be something other than ‘extreme Democrats’ – it cannot simply exist as the nominally radical wing of a fundamentally centrist party with a billionaire donor base. We have seen time and again that both the party leadership and the majority of its membership refuse to move anywhere but to the right, since the left is considered a captive constituency (when it’s considered at all). And when you endorse or lend your public efforts to a political brand that you have no leverage over and that has made no effort to address your concerns, you will only end up saddled with the baggage of decisions in which you had no input.

Only the most stubborn leftist contrarians would outright deny that Zohran’s victory was preferable to Cuomo’s, even if his policies are unlikely to get passed. But ultimately, the answer to “how should radicals approach elections” is to stop investing them with so much symbolic significance – and maybe just enjoy the memes.

I mean, it's arguable that posturing and virtue-signalling around voting have more of an impact on what happens than actually voting, since talking about voting is a far less atomised form of activity than voting itself. What sort of persona you perform around the question of voting is to do with your social embeddedness and contributes to the general ambience and vibe in which voting takes place, which is a much better candidate for the kind of agency that actually decides in an election than a series of individual sovereign decisions. Whereas what you personally actually do in the radical isolation of the voting booth is statistically virtually guaranteed to have no impact on anything.